RTPI Scotland has published a report examining performance and resources in the Scottish planning service. Complementing this report, Thomas Fleming (Intern Project Officer, RTPI Scotland) and Joe Kilroy (Policy Officer, RTPI) consider the limitations of performance measurement, the potential of open data and the possibilities that lay ahead for assessing—and maximising—the impact of planning.

Measuring planning performance has been on the agenda of local governments for decades (Faludi 2000; RTPI 2008; Sager 2011). With continued focus on processing times, application volume, approval rates, planning fee income to expenditure, the balance between the ‘3 Es’ of efficiency, economy and effectiveness had, for many, shifted to the detriment of a proper understanding of what planning delivers (see Houghton 1997). With the development of Planning Performance Frameworks in 2011, Heads of Planning Scotland (HOPS) have broadened these indicators with the ‘7 Ps’: performance, product, people, process, perception, policy and participation. Despite this, attention has largely centred on ‘economy’ and ‘efficiency’ within local planning authority performance: target-based performance measurements have been the most controversial and—perhaps, most straightforward—mean to assess the success of the service. In Scotland, these metrics might, controversially, soon serve as evidence bases for future resource allocation.

It is necessary to link ‘performance’ to changing resourcing levels, but this connection should be robust and adequately depict the role of spatial planning in effectively achieving policy goals. How do we measure ‘effectiveness,’ and how can we link it to our concerns with efficiency and economy? It may be helpful to consider these as mutually constituted: in short, efficiency and economy might be measured in light of effective planning processes and interventions, and the impact of planning decisions and priorities on varying geographical scales and over time. One way to buttress evidence and future-proofing planning’s effectiveness throughout the planning process is through open data.

What is open data and how might planning make use of it? ‘Useful and usable’ open data—or open ‘knowledge’—is defined by the Open Knowledge Foundation as “content, information or data that people are free to use, re-use and redistribute — without any legal, technological or social restriction” (https://okfn.org//). In theory, open data and open knowledge is important because it can help achieve social and economic value, increase transparency, and encourage civic engagement. Furthermore, the ‘Open Data Handbook’ identifies the following as ‘value-creating’ aspects of open data:

- Transparency and democratic control;

- Participation;

- Self-empowerment;

- Improved or new private products and services;

- Innovation;

- Improved efficiency of government services;

- Improved effectiveness of government services;

- Impact measurement of policies; and

- New knowledge from combined data sources and patterns in large data volumes;

Indeed, CIPFA (2014) argue that with continued developments in technology, local government services will become more ‘tailored’ and designed around information services to become much more attractive to users. More important than ‘data-for-the-sake-of-data’ is its role in empowering users and data creators to find solutions to urban problems. In an era in Scotland where the Government aims to make services more ‘people-centred’, it should be asked whether planning has gone far enough to follow its culture-change trajectory and embrace open data. Firstly, as a measure of improving accessibility to data by applicants, stakeholders or communities about planning applications or development plans, open data presents an opportunity to further democratise planning. It can serve as the basis for robust and dynamic analytical tools which can provide accurate and up-to-date information about places whilst empowering people and improving planning outcomes. This potential reflects the increasing importance for users to have greater involvement in decision-making processes and to have a greater voice in, and knowledge of, the provision of local services.

Secondly, whilst the RTPI continues to make the case for LPA resourcing, in the current climate of austerity the reality is LPAs have to do more with less. Data cannot do the work of planners, but there is potential for it to help achieve the ‘3 Es’. Councils are using technology and digital tools and approaches in ways that clearly demonstrate an impact both in terms of improved outcomes for citizens and financial savings. Data and technological innovation has been successfully combined with the intelligent use of customer insight and other complementary approaches such as demand management, and collaborative procurement. In an English context, for example, the London Borough of Lewisham’s web and mobile application ‘Love Lewisham’ enables residents to report environmental issues, leading to a 73 per cent reduction in graffiti, and a 33 per cent drop in call-centre activity, saving £500,000 over the past five years. Lewes District Councils using ‘pam’ collaboration software to enable staff across all partner agencies to work in a more joined-up way.

Across the world, digital civics is therefore becoming an increasingly important way, in theory, of improving local government services. Organisations like Nesta, data.gov, the Open Data Institute, and the open knowledge foundation are all supporting the reformation of public services—from the bottom up—around empowered users and shared data. Furthermore, online mapping (such as openstreetmap.com) is becoming increasingly prominent in providing multi-user-generated data on land uses, transport routes, environmental information, socio-economic data, local services, and more (see, for example, http://plenar.io/). For example, the ONS Scotland Green Map is a notable achievement in identifying every green space available to the people of Scotland. Locally, Glasgow’s ‘Open Glasgow’ initiative has produced over 400 data sets, providing information on everything from local services to electricity consumption. There have been hundreds of contributors—Glasgow City Council has provided data sets on, among other things, planning applications, housing information, and stalled spaces. The ethos of shared data has been used to improve application processes. For example, The West of Scotland Archaeological Service has produced a shared service GIS map to help applicants and planners on large geographical scales, providing information on sites of archaeological interest, thereby improving applications and decisions.

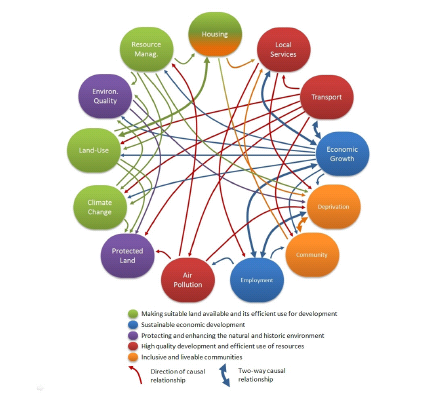

From the perspective of current LPAs in Scotland, open data can improve access to knowledge whilst also positively influencing planning decisions and priorities or increasing civic engagement, integrating multidimensional datasets with the everyday work of planners. Proposed outcomes of spatial plans could be measured against—and defined by—various data bundles, reflecting spatial planning’s multifarious relationship to society. In an English context, RTPI (2008) have identified a number of ‘key spatial planning outcomes’ and their interrelationships (see Report, Figure) and policy links. These broad indicators could be represented and through open data and could also include:

- Providing the status of planning applications and internal performance data;

- Resource (staff numbers, working hours and financing) allocation within planning services, income-to-expenditure by service, real-time cost recovery, etc.;

- Integrating e-planning, representations, and civic engagement through online mapping and data portals;

- Linking Single Outcome Agreements and Community Planning priorities to spatial planning interventions;

- Mapping existing and expected housing provision;

- Measuring and mapping localised energy use, waste, carbon emissions, etc.

- Representing changing demographic data, crime statistics, employment and health data over space and time;

- Creating metrics for user satisfaction or attitudinal data;

- Providing land ownership information, vacant or derelict land;

- Identifying sites of historical or natural significance;

- Mapping LDP action programme progress and sites of proposed infrastructure; and

- Up-to-date (active) travel information, ‘lines of desire’, hotspots, etc.

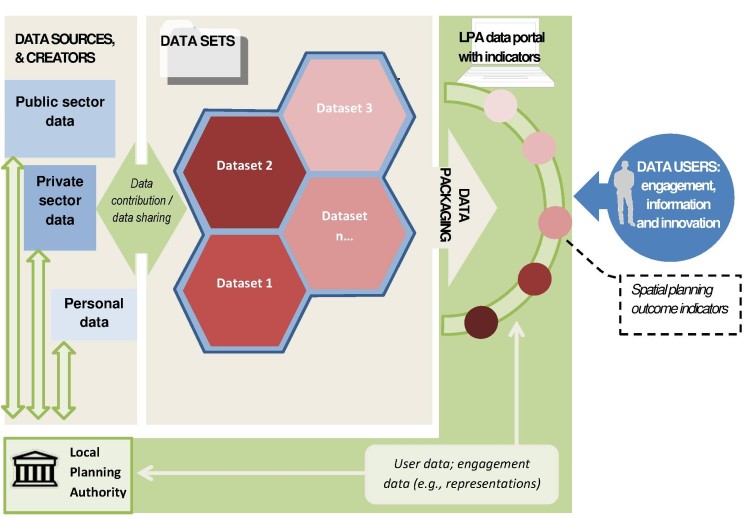

There are countless possibilities, but it is in the interest of all parties to link these and national indicator data to spatial interventions as a more robust indicator of planning performance. As noted, the methodological problem with performance measurements is their predominant focus on process and economy even though assessing whether the planning service is really delivering depends on measuring wide-ranging social, cultural, economic, and environmental factors. Yet, the data available to planners is not used optimally, nor does planning ‘give back’ to the data community as a matter of course. In addition, when considering planning performance from the perspective of process and economy, it becomes less concerned with broader positive impacts. Measuring ‘effectiveness’ requires that actors engage with diverse information about the built and natural environment and framing continuous civic engagement through data accessibility (see Figure 2). This creates a potential for an increasingly responsive and democratic service, demonstrating social and economic value in virtue of its connection to a digital ecosystem. (With increased interaction of multiple, spatio-temporally robust data bundles, it is conceivable that planning authorities will be able to produce analyses of their projected performance and outcomes based on observed relationships between inputs, outputs and impacts. Yet, this depends on planners and researchers demonstrating links between planning interventions and broader socio-economic, demographic or geographic changes over space and time.)

It might be that planning continues to be assessed in terms of its ability to process applications and create plans on time, and on budget. Yet, open data presents an opportunity to broaden the performance horizons, potentially leading to better outcomes, and re-thinking how we continue to define and assess ‘good performance’. As professionals defined by creativity and tempered by hard evidence, it is exciting to consider how planners in Scotland will achieve this.